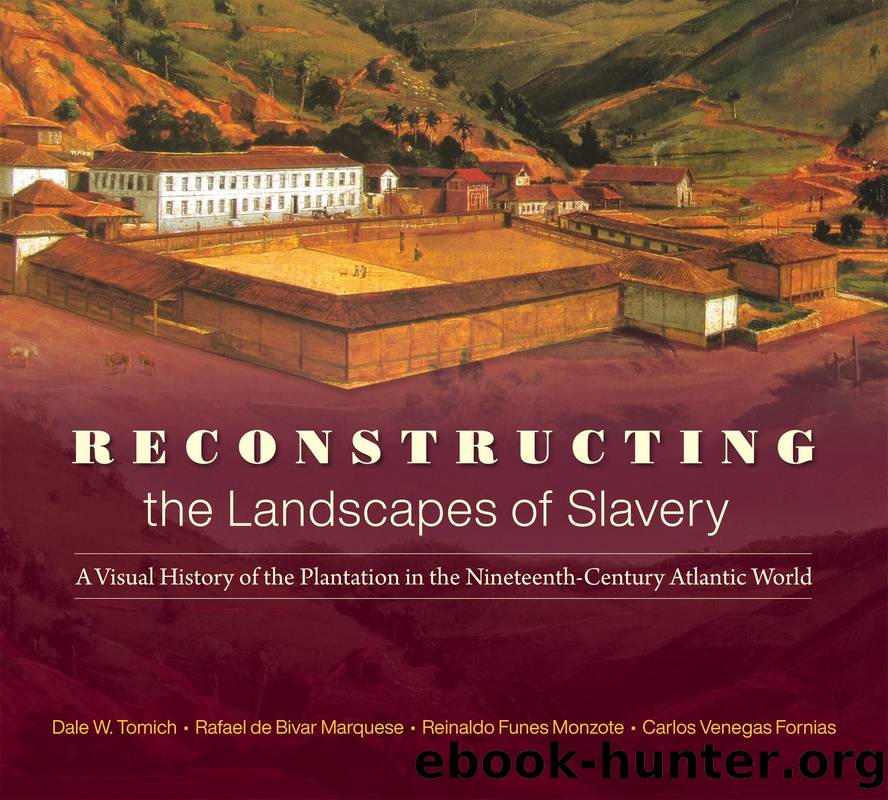

Reconstructing the Landscapes of Slavery by Dale W. Tomich Rafael De Bivar Marquese Reinaldo Funes Monzote and Carlos Venegas Fornias

Author:Dale W. Tomich, Rafael De Bivar Marquese, Reinaldo Funes Monzote and Carlos Venegas Fornias

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of North Carolina Press

Published: 2021-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

Figure 4.05. Cotton gin house, Killarney plantation, Concordia Parish, Louisiana. Lemuel Parker Conner Family Papers, Mss 1403, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Louisiana State University Libraries, Baton Rouge.

Figure 4.06. Gin house and cotton press. 1899. Tompkins, Cotton Mill, Commercial Features, 5.

A variety of presses of local manufacture were in use. The screw press pictured in Waudâs Scenes on a Cotton Plantation and in figure 4.06 could be found on small and medium-sized plantations. Made of wood, the large screw mechanism was turned by a mule or horse. Its great disadvantage was that cotton lint had to be carried from the gin to the press. It took much more time and effort to bale the cotton, and work could be done only in fair weather.26 More popular on the larger plantations of the Natchez District was a horizontal press with two heavy wooden screws. Both gins and presses were installed in the same building and could be driven from a common power source, whether draft animals or steam engines. The horizontal configuration of the screws allowed the press to fit easily under the floor of the gin stand.27 Cotton was initially packed in long cylindrical bags that weighed about 300 pounds. This method was abandoned in the Natchez District when local mechanic and gin wright David Greenleaf invented a practical cotton press. The use of compressed bales facilitated transportation of the massive quantities of cotton that were produced and protected them from dirt, water, and fire. Whichever type of press was used, the cotton box was lined with Kentucky hemp bagging to cover the upper and lower side of the bale. The cotton lint was then packed into the box and compressed into a solid mass. Ropes were passed around the bales to secure the covering and tied, and the openings in the hemp bagging were sewn together with twine. The screw was released, and the cotton swelled within the ropes. The bales were weighed, numbered, and marked with the name of the planter and his plantation. They were then hauled by wagon or cart to the nearest shipment point and consigned to the planterâs agent or a commission agent. The weight of the bales was not uniform. Bales pressed in Mississippi weighed between 400 and 500 pounds, in contrast to those in the south Atlantic states, which generally weighed between 300 and 325 pounds. Shipping charges were calculated by number of bales rather than by weight. The larger bales resulted in lower transportation costs.28

Development of the Natchez cotton frontierâs extensive and fertile lands depended on securing an adequate supply of labor. This demand for labor was satisfied by the interstate slave trade. Between 1820 and 1859, over 300,000 slaves from Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas endured the âsecond middle passageâ that carried them to Mississippi and Louisiana.29 The flux of slaves transported to Natchez for sale followed closely upon the fortune of the cotton economy. It rose with the rapid expansion of cotton cultivation during the 1830s, subsided during the depression decade of the 1840s, and rose again with boom of the 1850s.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1707)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1625)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1430)

Tip Top by Bill James(1416)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1376)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1354)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1304)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

American Dreams by Unknown(1286)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1274)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1212)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1174)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1126)